Institute Employees and Domestic Personnel

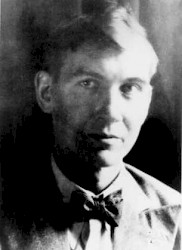

Karl Giese

1898 – 1938 – Institute archivist

Giese met Hirschfeld around 1920 and became his friend and student. In the inner circles at the Institute, Giese was considered Hirschfeld’s “foster son” and “woman of the house”. resided at the Institute with Hirschfeld, served as his secretary, held lectures, gave tours, and was head of the Institute archives.

This “dedicated, earnest, intelligent campaigner for sexual freedom had an extraordinary innocence. … “ reminisced Isherwood about Karl Giese, “Christopher saw in him the sturdy peasant youth with a girl’s heart, who long ago had fallen in love with Hirschfeld, his father-image. Karl still referred to Hirschfeld as ‘Papa.’”

Biographical data:

Giese grew up in a working-class family.

After a lecture by Hirschfeld on homosexuality, Giese visited him in 1920. That marked the beginning of-in Hirschfeld’s words- “a physical, psychological bond”.

When Hirschfeld did not return to Germany in 1932 after his world travels, Giese followed him and encountered Hirschfeld’s new companion, Li Shiu Tong. Despite occasional bouts of jealousy, they succeeded in having a ménage à trois during their exile in France. Hirschfeld declared both lovers as his heirs.

Giese was forced to leave France in October 1934 due to a “bath house affair”. He went to Vienna and subsequently to Brno. He was later able to return to Nice.

Giese evidently never came into Hirschfeld’s inheritance. He lived in poverty in Brno and committed suicide in 1938.

Rudolph R./Dorchen

Domestic (male/female) and patient

Rudolph, who even early on in childhood – displayed a “tendency to act and carry on in a feminine way”, was castrated at his own request in 1922.

He worked as a domestic at the Institute, dressed as a woman and generally called Dora.

Hirschfeld affectionately called her Dorchen (little Dora) and published her transformation process as a transvestite in his work on gender studies “Geschlechtskunde”. Institute physician Felix Abraham published Dorchen’s gender transformation as case-study: “Her castration had the effect – albeit not very extensive – of making her body became fuller, restricting her beard growth, making visible the first signs of breast development, and giving the pelvic fat pad… a more feminine shape.”

In 1931, when Dora, is about forty, her penis was amputated by the Institute physician Dr. Levy-Lenz, and then an artificial vagina was surgically grafted by the Berlin surgeon Prof. Dr. Gohrbandt. Dorchen was one of the first sex changes altogether.

The sexual physician Dr. Levy-Lenz, who joined the Institute in 1925, recalls the domestic personnel as follows:

“It was, moreover, very difficult for transvestites to find a job.(…) As we knew this and as only few places of work were willing to employ transvestites, we did everything we could to give such people a job at our Institute. For instance, we had five maids – all of them male transvestites, and I shall never forget the sight one day when I happened to go into the Institute’s kitchen after work: there they sat close together, the five “girls”, peacefully knitting and sewing and singing old folk-songs. These were, in any case, the best, most hardworking and conscientious domestic workers we ever had. Never ever did a stranger visiting us notice anything…”

Adelheid Rennhack (born 1909)

Adelheid Rennhack was active at the Institute from summer 1928 to its close in early summer 1933, and was responsible for the entire in-house organization.

After finishing school, she learned tailoring from her mother in Stolp i. P. In 1927, she came to Berlin and first worked in a household in Spandau.

In the Institute her duties included the maintenance of the reception- and social rooms, care for the guests and patients who were housed in the upper floor of the villa, tableside service, maintenance of the laundry and cutlery, and any necessary shopping. Now and again she sat at the reception desk. Vis-à-vis her activity in the Institute, Adelheid Rennhack was the first contact person for many patients in the Institute, and for many she became a good friend.

As many other employees, Adelheid also lived at the Institute. In addition to room and board, she received a salary of 30 Marks per month. Her work hours were from 7 AM to 6 PM.

Additional Employees and Domestic Personnel

“Like the director himself, the small number of employed by the Institute (including domestic and office workers) appear to be homosexual. And there was a young man, a supposed student, evidently feeling quite at home, who left a strong impression of being homosexual. Of course, no evidence of any improper conduct could be established”, senior medical health officer Schlegtendal wrote in a report of 1920 on a visit to the Institute on behalf the Ministry of Public Welfare.

Caretakers

- P. Schulz (1920), gateman

- M. Straube (1921), toolmaker

- Anton Sablewski

employed 1922-27 as plumber and caretaker. He was also the house “slide and film operator.” His wife Margarethe Sablewski (née Harendt) applied for a liquor license in 1922 for the Institute’s front garden. This request was denied by the Surveyors’ Office. - Andreas Janclas (1928)

- Ernst Kloß (1929)

- Erich Wenslaff (1932)

Housekeeping

- Hinrike Friedrichs employed 1927-33 as the Institute’s household-manager.

- Frau Krüger employed from 1926 on; cook in the communist shared apartment of Willi Münzenberg, Babette Groß, Heinz Neumann (among others) in the Institute.

Babette Groß remembers:

“At the same time that he recommended this home, Magnus Hirschfeld recommended Frau Krüger, a former chief cook at a Mecklenburg estate as well as an occasional aid for Hirschfeld. Every morning she came with her snow-white Pomeranian from Wedding and cooked for us. She knew our exotic guests, but she was discrete and was not surprised about anything. Politically she was more than likely not of the same opinion as Münzenberg, but she was enchanted by his charm. In 1933, at the interrogations by the police during the trial surrounding the burning of the Reichstag, a number of photos of our visitors were presented to her. She remained true to her statement that she did not know them. She believed that she had seen Dimitroff, because she had made him coffee often.” - Erwin Hansen In 1930, as arranged by Karl Giese, Erwin Hansen was employed as a cook and housekeeper for the archaeologist Turville-Petre, who was living at the Institute.

“Erwin was a muscular giant of a man with short-cropped blond hair and used to be in the army. Now he was playing the part of the ‘girl Friday’ and getting on the fat side,” Christopher Isherwood recalls. “He was forever grinning at Christopher provocatively. Sometimes he even pinched his bottom. But Erwin was a Communist. So his non-bourgeois manner was not really spontaneous but, rather, a part of how he saw himself politically.” - Erwin hired a boy named “Heinz” as additional help. After the plundering of the Institute in May 1933, Isherwood, Heinz, and Erwin Hansen went to Greece to join Turville-Petre on the [rented ??] island of St. Nicolas, near Athens. After returning to Germany, Erwin was reported to have been arrested by the Nazis and to have died in a concentration camp.

Reception

Helene Helling (1930-34), 1 a widow, moved into the Institute as a tenant “After living there for a while,” Ellen Baekgaard recalls, “she saw how disorderly things were in the private house, and so she one day had a desk put in the entrance hall and there […] she settled down, and she also had an internal telephone connected on her desk. From that day on, noone dared enter without an appointment […]”

Mrs. Helling was not employed by the Institute, nor was she on its pay-roll. She simply belonged there. Around 1930, she was a middle-aged woman, or rather lady, a perfect lady in the real sense of the word.

She sympathized with the Nazis after they had raided, ransacked and plundered the Institute in May 1933, and she stayed on there until 1934.

Administration

- Joachim Schreiber (in 1924)

He managed the Ernst-Haeckel-Hall of the Institute. - Arthur Röser (1926-33)

He overtook the management of the Ernst-Haeckel-Hall by early 1926 (at the latest). By 1933, Rösler had become a Nazi. - Friedrich Hauptstein

As from 1924, he worked temporarily as secretary of the Institute-based office of the “International Conferences on sexologically based Sexual Reform,” and then became the Institute’s administrative head. In 1933, he was among the coworkers at the Institute who proclaimed their loyalty to Göring in writing.

Doctor’s help

Ewald Lausch began working in the Institute’s radiological department for Dr. Schapiro in 1924. He dissociated himself politically from Hirschfeld in the early 30s.

Lausch was characterized as a Nazi by all who knew him. He also signed the declaration of loyalty to Göring.